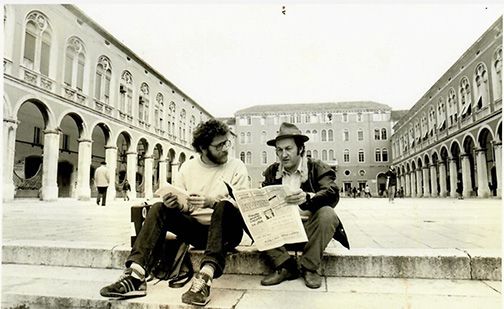

Hospitality and interview: Republic Square, Split, Croatia, 1988

Vladimir Zorić (Serbia)

Richard’s Unconditional Hospitality

In French, the word hôte means both “host” and “guest.” This may seem odd because in everyday life, as well as in politics, hospitality is based on a clear distinction between the host and the guest. In Kant’s famous formulation, global hospitality means that everyone should be welcome to visit everywhere, but by that fact alone one should not be entitled to stay, as this would erase the boundary between the host and the guest. But Derrida saw the ambiguity of hôte as a linguistic token of a very different, unconditional hospitality. In unconditional hospitality, the host and the guest open up to each other to such an extent that they swap roles, and willingly so. The capacity of the host not merely to let in the Other, but also to integrate it, is a barrier against every form of dogmatism, be it the dogmatism of one’s own subjectivity or that of one’s own nation.

Ever since I met Richard, he has made me think of precisely this higher, radical kind of hospitality. I have never visited Richard at his home in Cambridge. Maybe it has been precisely this lack of spatial setting in our encounters that has made it easier for me to observe that he has actively sought to make me feel part of his spiritual home. To paraphrase Derrida, he gave me, as a new arrival, all of his poetic home and his language, without asking for anything in return. But my point goes beyond hospitality in our personal relations; I am sure others have benefitted from this special hospitality no less than myself.

On this occasion, I want to acknowledge the radical hospitality he has practised, and disseminated, in my native land. Over several years, in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s, Richard hosted major poets, including from my old country, at the international Cambridge poetry festival. It is very fitting for a man such as Richard, who has been so willing to give unconditional hospitality to others, to also search for beacons of that unconditional hospitality in other people and other lands. He found one such beacon in Yugoslavia and called it, in his poetry, a special quality of light in the Balkans. In Richard’s essays on Yugoslavia, the word “hospitality” crops up over and over again: he celebrates Yugoslavia’s guileless poetry festivals, convivial dinners with his Yugoslav friends, their spontaneous desire to translate, i.e. to host, his poetry in Serbo-Croat. Precisely by being a guest in Yugoslavia, Richard also discovered a new way of being a host. In Belgrade, he hosted poetry workshops for Yugoslav schoolchildren and thereby assisted the birth of poems in another language. In the town of Kragujevac, at the site of a massacre of an earlier generation of schoolchildren, he hosted a blue butterfly, which landed on his hand, and transformed his poetic vision. In Cambridge, he hosted, in his memories, his deceased Yugoslav friends, and an entire vanished country, Yugoslavia. In other words, Richard initially arrived in Yugoslavia as a guest, but owing to unconditional hospitality he soon turned into a host to a linguistic and metaphysical Other which ultimately made him experience his previous self―his own language, his own hand, his own past―as a guest. The Balkan light has thus been a counter-reflection of Richard’s own light, an ambiguous as well as liberating experience.

The human catastrophe of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990’s uprooted communities and made many Yugoslav citizens guests in different foreign countries (as refugees and émigrés), or otherwise made them feel like guests in their own, significantly contracted countries (as internal exiles). I wish more former Yugoslavs could have followed Richard’s lead and granted unconditional, rather than selective, hospitality to one another. In his visits to Belgrade since the war, Richard has appeared as less of a guest and more of a host to his own traumatised hosts, someone who has sought to give them the solace of empathy and a glimmer of hope. Nowadays, as we reflect on Richard’s experience within/without Yugoslavia, and as we read his bittersweet recollections, we discover new, less estranging ways of being guests in our own pasts.

Back to introduction here.

Back to overall start page here.